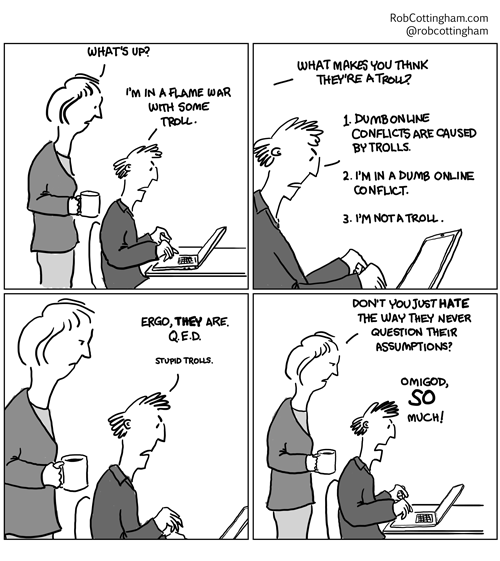

There is no shortage of hot-button issues to yell at other about on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. (Maybe less so on Pinterest. The comments seem a lot more civilized there.) And it’s really, really easy to decide the other party in a shouting match is a troll, because nobody could seriously believe the outrageous crap they’re spouting, right?

Enter Alexandra Samuel’s “How to Survive an Online Sex Scandal,” spurred by a recent Canadian controversy. (To my American friends who think that’s an oxymoron, how dare you?!)

It’s not, as the name suggests, a reputation-management handbook. Instead, it’s a survival guide for those of us who don’t want to get swept into acrimonious online disagreements over highly-charged issues. There’s a lot of wisdom in there to digest, but this passage in particular jumped out at me:

But the most powerful tool, and the most fundamental protection, is simply to recognize what’s going on when we explode online. We explode because we come to each of these debates with different ideas about the social media spaces in which our conversations unfold, with different ideas about who is in our online community, and with different levels of investment in the issues at hand.

Often, a troll isn’t a troll at all—at least, not in the classic definition of someone who’s just trying to stir up sturm und drang. Often, Alex points out, they’re just coming to the table with much different expectations and assumptions: “If you’re approaching a conversation as a citizen journalist, and I’m approaching it as a therapeutic process, you’re likely to get frustrated, and I’m likely to get hurt.”

Add to that the fact that we’re all notoriously awful at judging each others’ motives in conflicts, and it’s a recipe for degeneration into shouting.

There are genuine trolls out there, of course. There are also abusive bullies and people who’ve never learned to have a disagreement without waging total war. But I’m going to take a few breaths in my next online dust-up. And even if I can’t see things from the other person’s point of view (which, honestly, we usually can’t), I can at least try to identify the assumptions and expectations they have coming into the conversation. It might lead to a more productive discussion—or at least a shorter one.

P.S.—Longtime readers will know this already. Disclosure: I’m Alex’s husband.

2 Comments

“Often, a troll isn’t a troll at all—at least, not in the classic definition of someone who’s just trying to stir up sturm und drang.”

It’s easy to identify trolls, and to distinguish them from people who just want to “stir up” the conversation.

Trolls have no respect for others, especially others who hold a different opinion or preference than their own. They display their disrespect for others by resorting to insults, often swearing and using abusive language.

Trolls have low self-esteem, and their insecurities result a psychological disorder in which they believe that their subjective opinions and preferences in products are some sort of universal “truth”. Trolls feel that their egos are under attack if others have different choices in products than their own, in which case the trolls will harass them.

Almost always, trolls have low intelligence, and rather than presenting an argument objectively stating facts, they will give baseless opinions that have no bearing in reality.

There is a common saying related to trolls in online forums: “Don’t feed the trolls”.

But ignoring trolls only encourages them to continue being an annoyance to others, since there is no consequence to their abhorrent activities.

It is better to respond to trolls’ insults by replying to them in a calm and objective manner, and provide factual information (with references to the source) that obliterates the trolls’ ludicrous opinions.

This type of response accomplishes two things. It allows those harassed by trolls to bring facts and reality into the conversation (instead of just accepting the abuse and not responding), and it makes the troll appear foolish to others in light of the factual information given.

Responding this way will discourage trolls from continuing their disruptive and offensive attacks on others.

I can see where you’re coming from, Harvey, and while I think we may see this a little differently, we at least end up in the same neighbourhood: don’t respond to aggressive behaviour in kind.

Part of the problem (and I think Alex gets at this more persuasively than I do above) is that in the heat of the moment, it can be hard to tell if someone really is just trying to stir things up, or if they’re responding heatedly because they feel very strongly about an issue. (They may not even be aware that they’re speaking aggressively.) And that heat may not be directed at us, even if we feel singed; their anger may be aimed at some other party.

And I don’t know that we can say that trolls usually have low intelligence—partly because there isn’t a lot of reliable research into who trolls are. I’ve seen some very intelligent, manipulative people engage in trolling just for their own entertainment, and then boast about it afterward.

Thing is, “trolling” is fundamentally about motivation, and people tend to be both remarkably bad at accurately ascribing motives to others and mistakenly confident in our ability to do so. (Everyone else does, anyway; I’m awesome at it.) And I’m constantly seeing folks label unwanted or irritating behaviour as trolling, even when it’s entirely possible that the “troll” is perfectly sincere. (Maybe a jerk, but a sincere one.)

But as I say, we both seem to land in roughly the same place: returning fire is a losing strategy whether you’re dealing with a troll, a jerk or someone who’s feeling triggered and reactive.