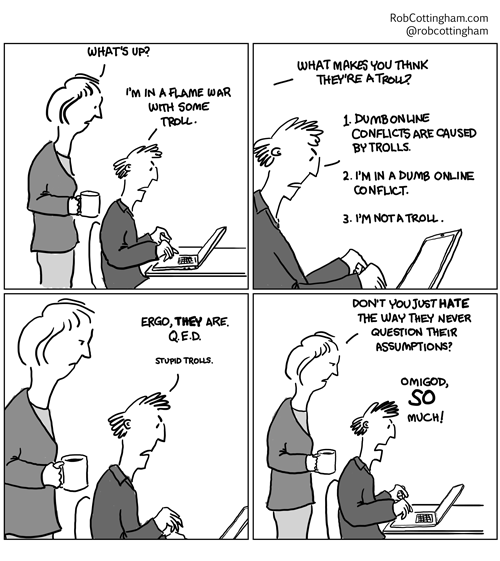

There is no shortage of hot-button issues to yell at other about on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. (Maybe less so on Pinterest. The comments seem a lot more civilized there.) And it’s really, really easy to decide the other party in a shouting match is a troll, because nobody could seriously believe the outrageous crap they’re spouting, right?

Enter Alexandra Samuel’s “How to Survive an Online Sex Scandal,” spurred by a recent Canadian controversy. (To my American friends who think that’s an oxymoron, how dare you?!)

It’s not, as the name suggests, a reputation-management handbook. Instead, it’s a survival guide for those of us who don’t want to get swept into acrimonious online disagreements over highly-charged issues. There’s a lot of wisdom in there to digest, but this passage in particular jumped out at me:

But the most powerful tool, and the most fundamental protection, is simply to recognize what’s going on when we explode online. We explode because we come to each of these debates with different ideas about the social media spaces in which our conversations unfold, with different ideas about who is in our online community, and with different levels of investment in the issues at hand.

Often, a troll isn’t a troll at all—at least, not in the classic definition of someone who’s just trying to stir up sturm und drang. Often, Alex points out, they’re just coming to the table with much different expectations and assumptions: “If you’re approaching a conversation as a citizen journalist, and I’m approaching it as a therapeutic process, you’re likely to get frustrated, and I’m likely to get hurt.”

Add to that the fact that we’re all notoriously awful at judging each others’ motives in conflicts, and it’s a recipe for degeneration into shouting.

There are genuine trolls out there, of course. There are also abusive bullies and people who’ve never learned to have a disagreement without waging total war. But I’m going to take a few breaths in my next online dust-up. And even if I can’t see things from the other person’s point of view (which, honestly, we usually can’t), I can at least try to identify the assumptions and expectations they have coming into the conversation. It might lead to a more productive discussion—or at least a shorter one.

P.S.—Longtime readers will know this already. Disclosure: I’m Alex’s husband.