I love the mania today for teaching kids to code. I’m glad it’s a lot easier than it was when I first started stringing commands together.

I love the mania today for teaching kids to code. I’m glad it’s a lot easier than it was when I first started stringing commands together.

When computers (in the form of the venerable Commodore PET) first came to Gloucester High School, I got the impression most of my teachers were scrambling to stay ahead of the geekier students, learning various BASIC commands a few days (or hours) before the more highly-motivated among us did.

I mostly learned it on my own time: staying very late at the school, worrying the hell out of my parents, entering line after line of code from magazines, and then tinkering with it to see what would change. Nearly everyone I know thought it was a little freakish of me. But something about this seemed incredibly compelling, even important—despite the fact that mostly what I was keying in were instructions for playing Hammurabi (“I beg to report to you, in the year 3, 0 people starved, 6 came to the city…”).

But something sticks with me from my Grade 10 Informatics class: a transparency my teacher threw onto the overhead projector that read “The man who knows how will have a job. The man who knows why will be his boss.”

(Okay, two things stick with me, and one of them is just how casual the exclusion of women from language was when I was a kid. )

Coding is very much a how activity. And I think it’s good to get some of that knowledge under your belt, and to understand the core concepts beneath it. If you’re into it, great; go a lot further.

But as Jeff Atwood wrote a few months ago, people drive cars all the time without knowing how fuel injection works; “By teaching low-level coding, I worry that we are effectively teaching our children the art of automobile repair.”

Learning to talk to the computer is the easiest part. Computers, for better or worse, do exactly what you tell them to do, every time, in exactly the same way. The people – well . . . you’ll spend the rest of your life figuring that out. And from my perspective, the sooner you start, the better.

I want my children to understand how the Internet works. But this depends more on their acquisition of higher-order thinking than it does their understanding if ones and zeroes. It is essential that they that treat everything they read online critically. Where did that Wikipedia page come from? Who wrote it? What is their background? What are their sources?

Learn to investigate. Be critical. Don’t just accept opinions you saw on Facebook or some random web page. Ask for credible data, facts and science.

That, to my mind, helps to get at the why. And with all due respect to my Informatics teacher, that goes a lot further than who gets the corner office. It’s part of being a citizen: not just in the formal sense, and not even just in the civic sense, but in the sense of someone who participates in the world around them – on- and offline – and helps in some small way to shape it.

Teaching our kids about variable scope in Java? That helps them become programmers. Helping them with the “why” – that helps them become adults.

(Photograph by Rama, Wikimedia Commons, Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr)

⌨️

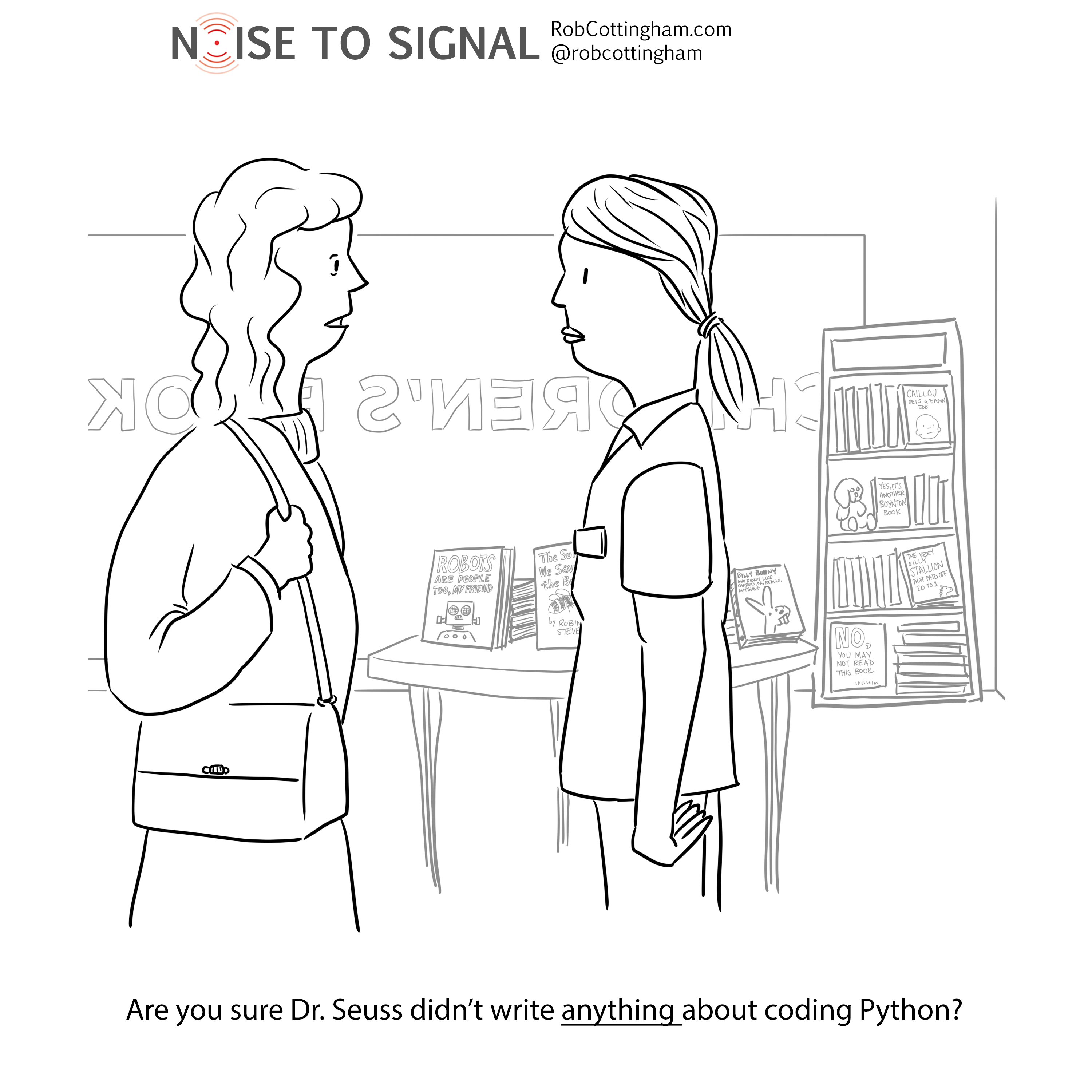

I drew this and six other cartoons about parents, kids and tech for Alexandra Samuel’s session at SXSW 2016, The Myth of the Family Tech Market. It’s based on her two-year study of how more than 10,000 North American parents manage their kids’ interactions with digital technology.

Find out more about Alex’s work around digital parenting here.