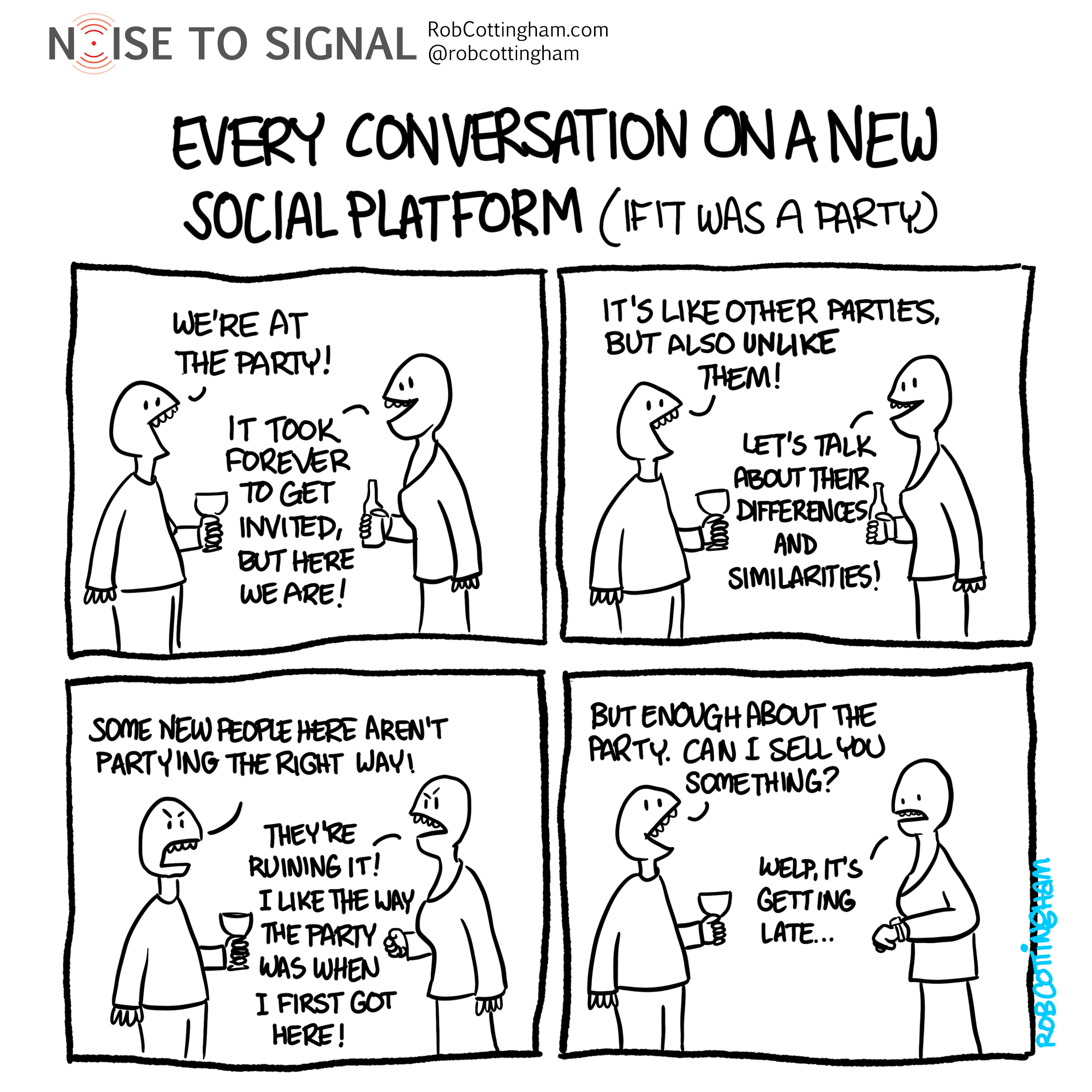

Oh, those awkward early weeks of a new social platform when so many of the conversations seem to be about the platform itself. This week, the new kid on the block is Threads, Meta’s answer to Twitter.

Scrolling through my feed on Threads, it seems three out of every four posts is either some variation on “So this is Threads,” advice for using Threads, reflections on the experience so far or predictions for Threads’ future.

Or a sardonic reflection on the fact that we all seem to be using Threads as a way to talk about Threads. Which is, let’s face it, kind of hilarious. (Hence the cartoon.)

Thing is, though? It’s also absolutely natural. If you and I were plunked down in unfamiliar surroundings, I’m guessing we’d be spending a lot of your early time there talking about those surroundings: observing, analyzing, speculating and even critiquing them.

One unavoidable topic when we’re talking about Threads: privacy. By now you’ve probably heard about just what a spectacular personal-data-land-grab Threads involves. It’s pretty much what the Facebook and Instagram apps already require you to fork over before you can start posting cat reels and such); a little more than Twitter; and a lot more than, say, BlueSky.

The privacy winner, though, is Mastodon. Here’s how they put it at Ars Technica:

Below is all the data collected by Mastodon that’s mentioned in the App Store.

*In the style of Taylor Swift.*

[Blank Space]

(And if you’re wondering whether you can find me on Mastodon, why yes, you very much can.)

As we’re adjusting to this latest meteor impact in our social media ecosystem, it’s worth considering that there may not be any one successor to Twitter. Maybe we should stop trying to figure out who will win that crown — because perhaps there shouldn’t be a crown in the first place.

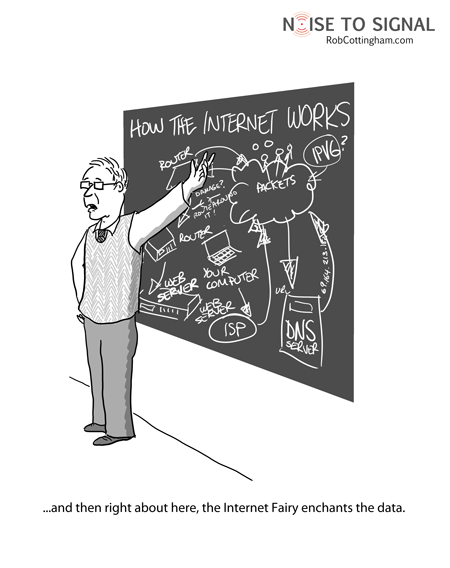

Threads’ makers are promising they’ll be connecting it before long to the Fediverse, a group of intercommunicating servers and services connected through a common protocol (thanks again, Evan Prodromou!) So the successor to Twitter might be not be one service, but thousands. Let a million servers bloom.

That holds just the faintest shadow of a glimmer of a spark of hope for the revival of the open Internet heralded in the early years of Web 2.0 — blogs and wikis and services large and small all talking to each other, and users being able to communicate across platforms instead of within walled gardens.

That’s a party I’d love to go to. I’ll bring chips.